I really do love my day job. I have the occassional opportunity to venture into interesting places that I am eager to share.

The herbarium at Singapore Botanic Gardens is one of such places. It is tucked at a corner of the sprawling compound and may not be easily noticeable to common visitors. Part of the herbarium, particularly the preparation area is open for public viewing via a glass window in the library.

Through the window, you can observe how the experienced technician mounts the herabium plant specimen by applying glue and adhering it to a rag-cotton archival-quality card. The specimen is then sewed onto the sheet for additional support before the information label is pasted on. This step of preparation is only one of the several steps involved in the herabium specimen making process.

Prior to mounting, other steps include collecting the plant specimen, preparing the sample using chemical treatment, preparing the information on the label and cataloguing the specimen in a database.

The widespread, scientific circulation of the herbarium specimen is precisely why it is so important to maintain a high level of accuracy and precision in each step of the preparation process.

In a nutshell, a herabium specimen is a physical sample of a known plant classified according to the modern Angiosperm Phylogeny Group Plant Classification System. The specimen is usually collected during a fieldtrip or a floristic survey. About 30cm of the plant, representative of its growth, including leave, stem, flowers and fruit is collected intact. Each collected sample is accompanied by comprehensive field notes and desk research. Information include the collector’s name, date of collection, collection number, locality, habitat and description of the plant habit, especially notes on field characters that cannot be observed on the dried specimen.

Famous herbarium collectors who had graced the shores of Singapore include the great naturalist, Alfred Wallace, best known for his work on the theory of evolution through natural selection in 1858, paralleling the work of Charles Darwin. He conducted extensive fieldwork in Borneo and Malaysia, using Singapore as his research base. Wallace’s herbarium specimens now reside in UK collections, such as his fern collection in Cambridge University spanning 33 species, 22 genera and 17 families. More information can be found at http://cambridgeherbarium.org/collections/alfred-russel-wallace-ferns/.

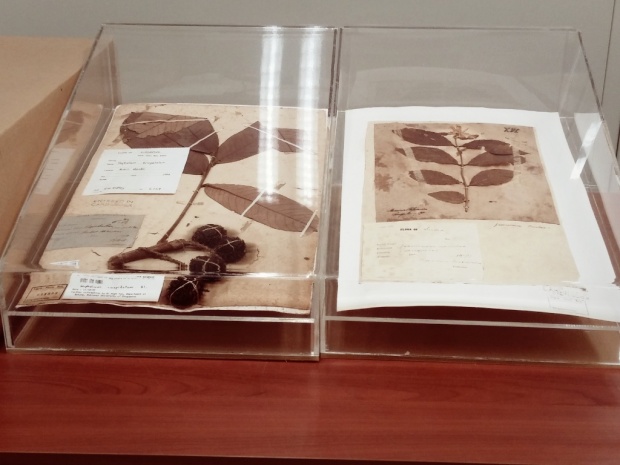

Another famous plant collector well known in Singapore is Henry Ridley, the first Scientific Director of Singapore Botanic Gardens from 1888 to 1911. He was known for the many years spent promoting rubber as a commercial product and his discovery in 1895 of a means of tapping which did not seriously damage the rubber trees. Due to his discovery and work, he was largely credited for establishing the rubber industry in Malaya and Singapore. Less well known, Ridley lived to a ripe old age of 100 and retired in Kew, where he continued to visit the Royal Botanic Gardens on a regular basis. He also bought back many herbarium and timber samples now stored in Kew. The picture below shows one of such sample which I had the privilege to hold when I studied in Kew.

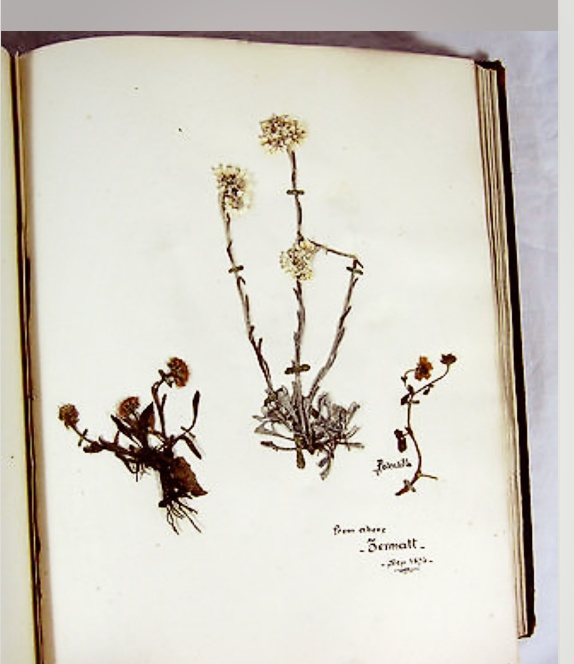

So how do herbarium samples relate to bookbinding? According to Duke University Herbarium (http://herbarium.duke.edu/about/what-is-a-herbarium), Luca Ghini, professor of medicine and botany at the University of Pisa during the 16th century, is credited with the invention of the herbarium. Traditionally, several plant specimens were glued in a decorative arrangement on a single sheet of paper. These sheets were then bound into volumes, stored in a library, and cited like books. Specimens were thus placed into a fixed order from which they could not be removed without destroying the specimens.

It was the famous Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus who advised readers of his Philosophia Botanica in 1751 to mount just one specimen per sheet and refrain from binding the sheets together. For storage of the mounted specimens, Linnaeus suggested a specially-built cabinet where individual sheets could easily be inserted at any place, removed at any time, and reinserted again anywhere in the collection. In contrast to the bound volumes of older herbaria, the order that Linnaeus’ herbarium cabinet brought to his collection was not fixed into perpetuity. This “internal mobility” of the herbarium could accommodate the arrival of new material and enabled the user to repeatedly rearrange that material to reflect new knowledge.

Hence, while not common, herabarium found as handbound volume do exist and are treasured. So, next time you stumble upon a volume of herbarium specimen, who knows, it might turn out to be quite valuable!